In stories of drift, organisations fail precisely because they’re doing well – but their measure of ‘well’ is based on a narrow range of performance criteria, which is often what the organisation gets rewarded on in its current political, economic or commercial environment.

When an organisation drifts toward failure, accidents can happen without anything breaking, without anybody erring, without anybody violating the rules they consider relevant, and seeing holes and deficiencies in hindsight won’t explain why particular actions and behaviours existed that way over time and were rationalised as normal. And it doesn’t help predict or prevent a future drift into failure.

In the words of safety researcher, Sidney Dekker:

“Drifting into failure is a slow, incremental process. An organization, using all its resources in pursuit of its mandate, for example, to provide safe air-travel, or deliver electricity reliably, will gradually borrow more and more from the margins that once buffered it from assumed boundaries of failure. The very pursuit of the organisation’s mandate, over time, and under the pressure of various environmental factors (most prominently, competition and scarcity), dictates that it does this borrowing – the organisation needs to be more efficient, do more with less, perhaps take greater risks. It is the very pursuit of the mandate that creates the conditions for its eventual collapse. The bright side inevitably brews the dark side – given enough time, enough uncertainty, enough pressure. Even well-run organisations exhibit this pattern.”

In stories of drift “local decisions that made sense at the time cumulatively become a set of socially organised circumstances and norms that make the system more likely to produce a harmful outcome“, so when we’re trying to understand why or how drift has occurred, we want to ensure our efforts are focussed on understanding what made sense to the decision-makers at the time? Why were the decisions of one or many thought of as normal? Why did nothing flag as report worthy?

Are Human Beings Rational Decision-Makers Or Are We Just Finding A Way to Make Sense Of Things?

With this in mind, let’s take a look at what influences our decisions at a local level and we’ll start with eliminating the idea that any one of us makes a rational decision because in complex socio-technical systems, of which we all work in, each person in the system does not have access to all the information they need to make a truly rational decision, at least that’s according to Classical Decision-Making or the Rational Choice Theory. This theory is the cornerstone of decades of decision-making research. It says that decision-makers are seen as ‘rational actors’; that is, we make choices based on logical analysis of all available options. However, having all the information in a complex system is literally impossible, we’re lucky if we’re able to understand or have all the information we need in our local setting, let alone in the entire system.

Not to mention, we make many of our decisions based on emotions that are driven by our perception of our environment.For example, we’ll make a decision based on how safe or secure we feel – an example is “fight or flight” – do we flee or stick it out.. We determine that based on how safe we feel.

Another example is how our need to feel accepted by people will influence our behaviour. Think about your kids or you as a young person … we will make bad decisions and hurt others to belong to a group. You might find your kid is called a bully by another parent, and while that might make you feel your kid is a bad person, it’s really just an example of your child making decisions based on the emotions they’re feeling.

When we don’t feel safe or secure, that stress or strain we feel not only impacts our behavior, but it impacts our nervous systems. An example is stress, it influences our behaviour and our physical and mental health.

Our values, assumptions and beliefs also influence our behaviour.

You get the picture, we are complex creatures, and because of this, how work gets done should never be thought of as something simple or one’s decision is common sense.

So out of dissatisfaction with the Rational Choice Theory, which to summarize assumes we have access to all the information we need to make the “right” decisions and that humans are pretty simple creatures who are not influenced by our environment or our emotions, came the Local Rationality Principle.

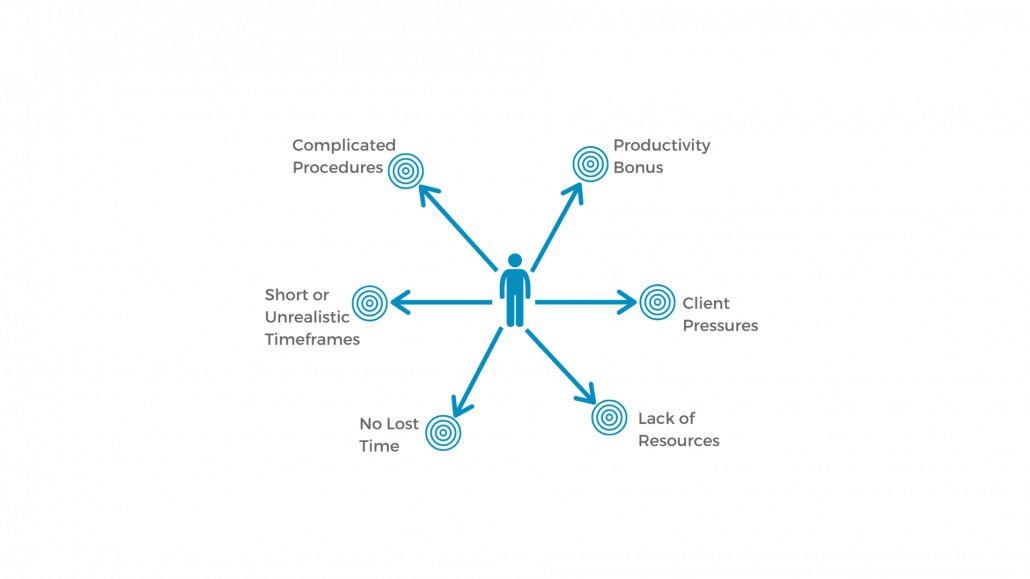

This theory suggests that people will do what makes sense given the situational indications, operational pressures, and organisational norms that exist at the time. That is, we will take our paradigms or world view, which are informed by our knowledge our values our history and our biases, we’ll reflect on our goals (which are often muddled because we’re constantly needing to address conflicting goals in any organisation), we’ll focus on, or be distracted by, what’s occupying our attention (for example, we might be upset with management that they didn’t give us the resources we requested and now we have an issue that would not have happened had we had those resources or we might be thinking we need to rush this job through because we have targets or incentives that need to be met), and finally, we’ll consider the nature of the data available to us at the time; that is, what’s actually happening right now around us, and then … we’ll try and find a solution that makes sense based on all of this. This is called the Local Rationality Principle.

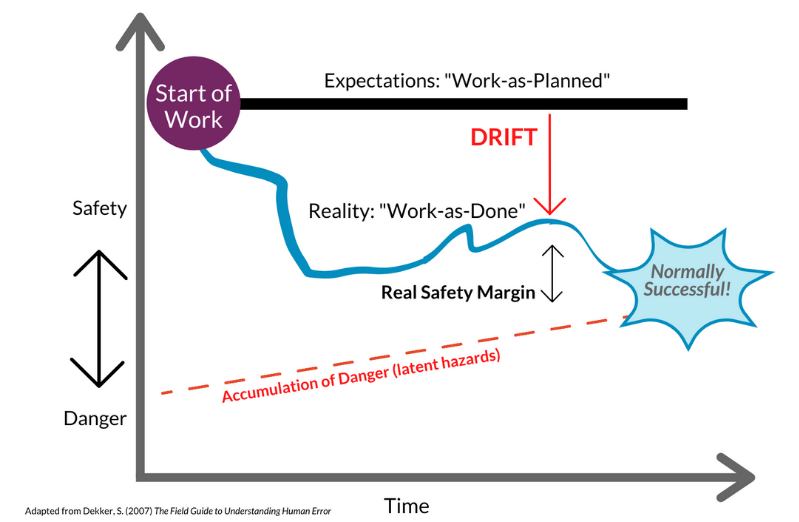

This happens to be where drift begins because locally sensible decisions about balancing safety and productivity – once made and successfully repeated – success being no incidents – can eventually grow into unreflective, routine, taken-for-granted scripts that become part of our worldview and this worldview can infiltrate people all over the organisation and how they make their decisions – it can become the organizational culture, not just a local sub-culture.

This is why normal everyday performance is not what is prescribed by rules and regulation, it’s more what takes place as a result of the adjustments we make – which we call work as done. Rules therefore become less important in informing our action; whereas, task demands, and environmental changes become more important. It’s also why it’s important for board members to understand where and how the board influences people’s perception of priorities.

Work-as-done is characterised by the kinds of adjustments, adaptations, variations, trade-offs, compromises, and workarounds that are hard to prescribe and hard to see from afar, but can become accepted and unremarkable from the inside. Mostly, such variability is deliberate, but sometimes it’s unintended.

Drifting Towards Danger

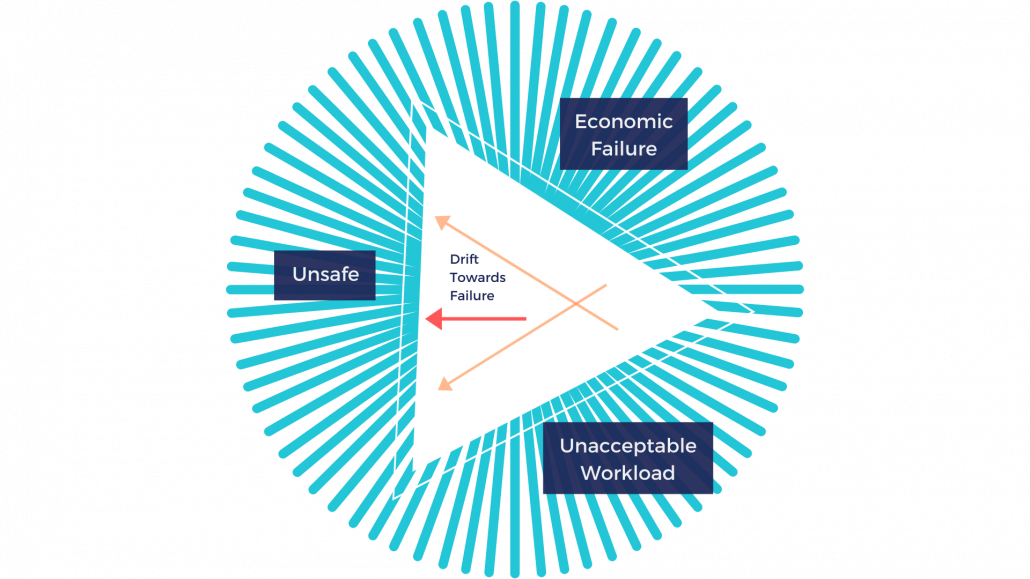

Pioneering safety researcher Jens Rasmussen illustrated these competing priorities and constraints that affect all socio-technical systems in his ‘Migration Model’. The model shows that operations are consistently trying to balance profitability, safety, and resources; more specifically that workers’ workload is feasible. These days we’d certainly add mental health into that safety category. There’s no way around these constraints, there’s only room for manoeuvring inside the space.

The pressures and constraints play out like this: the competitive environment encourages us to focus on short-term financial success and survival, rather than on long-term criteria (including safety). Workers will also continually seek to maximize the efficiency of their work, part of that will be to reduce their workload, and this is even more encouraged by conflicting organisational goals that promote “cheaper, faster, better”. These pressures push work to migrate towards the limits of acceptable (safe) performance. Incidents occur when the system’s activity crosses the boundary into unacceptable safety. The problem is, the boundary of safe performance is rarely easy to define before an accident, and it can move over time due to changes in the organisation.

Rasmussen called this drift towards danger where the systemic migration of organisational behaviour toward an accident will happen under the influence of pressure toward cost-effectiveness in an aggressive, competing environment. From the inside, decisions look normal, and making trade-offs in the direction of greater efficiency is nothing unusual, in fact many organizations reward it, and efficiency is also an adaptive response to scarce resources and production, but these trade-offs lead to departures from the norm, becoming the norm. Seen from the inside, deviations become compliant behaviour – it becomes the new paradigm for those in the organisation as to how work is done. It should therefore be no surprise that the trade-offs that people are making in the system are not necessarily done consciously, in fact these influences gradually become pre-rational, or norms that we take for granted and we bring to work with us.

The problem with drift is that it’s difficult to see until it’s already happened. Drift tends to be a slow process, with multiple steps that occur over an extended period where each step is usually small enough that it can go unnoticed, with no significant problems until it’s too late, which is why deviances are not report worthy and everything seems normal – this is referred to as an incubation period, where latent / dormant hazards accumulate.

Drift is paradigm shift because there’s a tendency to think that when the organisation experiences failure, that something must be ‘broken’, but the reality is that drift does not happen because of people’s lack of attention or knowledge; drift is a natural phenomenon that affects all types of systems organisations. People are complying with the emerging, local ways to accommodate multiple organisational goals.

In Part 2 of this series I’ll walk you through the first of three ingredients to the Local Rationality Principle – or simply put, how people make sense of things and some governance tips.

Welcome!

I’m Samantha

I help board members succeed in the boardroom and make a positive impact on the health, happiness and resilience of society through their effective leadership and governance of safety, health and well-being.

RESOURCES

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE…

FEATURED CONTENT

[text-blocks id=”4249″ plain=”1″]

Let us know what you have to say:

Want to join the discussion?Your email address will not be published.