Costa Concordia

I’ve been watching a really good webinar series as of late hosted by the New Zealand Institute of Safety Management. It’s a 5-part look at the investigation of the capsizing of the Costa Concordia cruise ship back in 2012 by Safety Investigator Nippin Anand. I’m sure you’ll recall this tragedy where the Costa Concordia capsized off the coast of Italy, specifically off the Tuscan island of Giglio (Jill-Lee-O) and resulted in the deaths of 32 people.

You might also remember the captain, Francesco Schettino who was ultimately blamed for the incident and dubbed “captain coward” by the international media for being accused of abandoning his ship before all the passengers and crew were evacuated.

After a 19-month trial, Schettino was found guilty of multiple charges of manslaughter, as well as other charges related to the ship’s capsizing. Schettino was the ONLY person put on trial as the owner of the ship entered a plea bargain in 2013 by accepting partial responsibility and agreeing to pay a one-million-euro fine. Five other Costa Concordia employees received non-custodial sentences after also agreeing to plea bargains early in the investigation.

Schettino was not even offered a plea bargain and he was sentenced in 2015 to 16 years and one month in jail.

A year later Schettino appealed the decision claiming that he was used as a scapegoat for the entire disaster. His lawyer was quoted saying that “[Schettino] hopes this trial can return to what it should be, a process focused on the search for the truth and not an analysis of his person”.

And that is where I want to focus.

There are many different angles and perspectives that we could look at this incident from, such as the owner’s perspective, the captain, the helmsman who steers the ship, the coast guard who conducted the rescue, the maritime industry, the prosecution, the safety profession, but we’re not going to delve into any specific one.

What I do want to focus on is our insatiable desire, when an incident occurs, to find someone responsible or something that’s broken, that ultimately caused the incident to occur.

The presumption is that if we find the culprit, or the bad apple, or that broken part, we can fix the problem and prevent that incident from occurring again. Of course, all of this is done with the best of intentions, that is, we’ve done what is morally right by trying to prevent further harm.

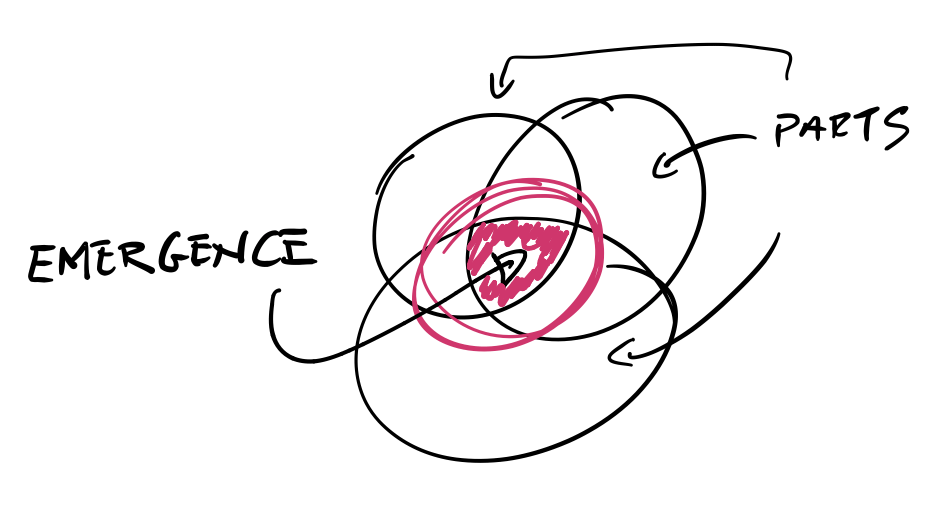

Emergence

But that need or desire to find someone responsible or something that’s broken, closes off our mind and our willingness to truly understand how safety AND incidents actually emerge in complex systems.

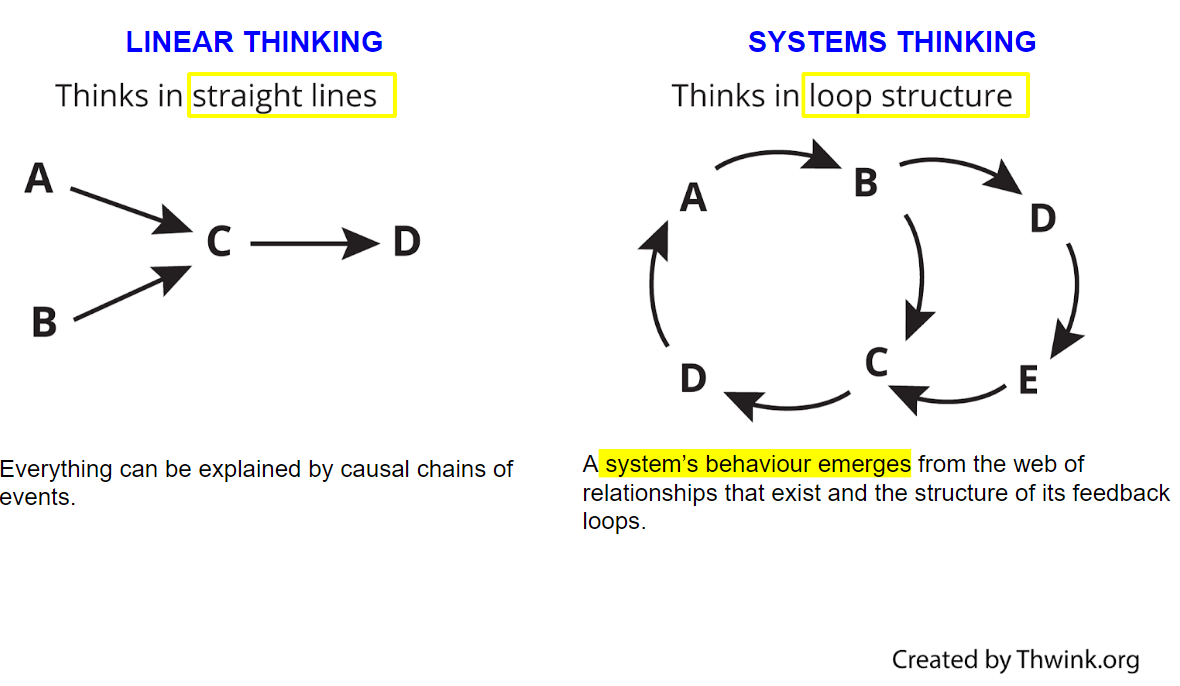

Emergence is a characteristic of complex systems and it means that when we’re looking at incidents we can’t simply break down the system in which we work or the organisation into parts and then see how those parts lined up to contribute to an event or incident. This is what’s called linear thinking; that is, Event A causes Event B, which causes Event C … you get the picture.

Many of you watching will know of James Reason’s Swiss Cheese Accident Causation Model … but even that model has us looking at incidents as a sequence of events. That is if latent hazards, or the holes in the cheese line up, it creates a pathway to an incident.

But in complex systems, linear thinking is not possible because the relationship between the parts, like the people, the processes and policies and procedures, is more complex which And it means we can’t look at the behaviour of individual parts to explain the behaviour of the whole.

But that’s what many people will do when they’re trying to understand how something happened – they try to find that one root cause.

And who can blame them, because this is how most of our incident or accident causation models have been designed. And it’s how many investigators will unfortunately frame their findings in order to give you a reason as to why something has happened, why this tragedy has occurred and what you can do to prevent it from occurring again.

In fact, the Italian maritime industry concluded its investigation in this way.

Here’s an excerpt from the report, but bear in mind, the report is a translation from Italian to English.

“In conclusion it is needless to put in evidence that the case of the Costa Concordia is considered by this Investigative Body (and we believe by everyone in the maritime field) – [that’s a pretty big assumption] [that this is] a unique example for the lessons which may be learnt … [so it’s true, we can learn a lot of lessons from this incident, but they go on to say] despite the human tragedy and the Master’s unconventional behaviour, which represents the main cause of the shipwreck.

They want on further to say:

“It is worth to anticipate, closing this summary, that the human element is again the root cause in the Costa Concordia casualty, both for the first phase of it, which means the unconventional action [that’s in reference to the captain’s behaviour] which caused the contact with the rocks, and for the general emergency management.”

Even the owners of the Costa Concordia ship, Costa Cruises, stated that “there may have been significant human error on the part of the ship’s master, Captain Francesco Schettino, which resulted in grave consequences”.

Hindsight bias

It’s easy to point blame when we’re looking at incidents with hindsight. But hindsight bias can make us think and see things more simply or more linearly.

When you invite hindsight bias, not only are you then looking for what is broken but you’ll be under the false assumption that should the part be fixed or the person be fired, demoted or re-trained, that you’ll be preventing the incident from occurring again.

Affording blame to individuals as the cause of incidents might meet our need to find someone accountable and show that we’re doing the right thing to prevent another occurrence, but it’s simply not the case.

The thing is, in complex systems, which, mind you, we all work in, safety and incidents are emergent properties. This means, even with our best efforts, we cannot understand exactly why an incident has occurred on the basis of looking at individual components, because in complex systems, individual parts do not represent the whole. Put simply, blaming an individual like Schettino will not prevent a future incident, and looking at his actions only, will not explain why or how the incident occurred.

Furthermore, in complex systems, nothing has to be broken and there doesn’t have to be anyone at fault for an incident to occur. In fact, all the components in the system and the people can be working as intended and an incident can still occur.

You’ll recall I said earlier that Schettino wanted the trial to return to what it should be, a process focused on the search for the truth and not an analysis of his person.

The reason I highlighted ‘truth’ here is because, with so many people’s interpretation of what happened that day, and how those on the ship interpreted the situation AT THE TIME amongst all the chaos and with their own mental models of what was happening, there’s an argument that in complex systems there is no truth or facts, just people’s perception of how things happened.

At the beginning of Anand’s masterclass, he continually stressed the point for participants to keep an open mind. And I encourage you to do the same when you’re reviewing an incident investigation, particularly incidents where it feels so clear and obvious that there is someone at fault.

In trying to understand what happened, don’t look for what was broken, or whose to blame for acting negligently or assume that someone’s actions were void of common sense … the question is NOT ‘why why they did they do or didn’t do ___?’, it’s WHY DID WHAT THEY DID MAKE SENSE?!

I’ve found that there are many parallels between Anand’s investigation and Scott Snook’s investigation of the accidental shooting down of two US blackhawk helicopters by two US F-15 fighter jets in 1993. Snook said each time he went to analyse the data, he became “hot and suspicious”, but each time he came out “sympathetic and unnerved”. He said “If no one did anything wrong; if there were no unexplainable surprises at any level of analysis; if nothing was abnormal from a behavioral and organisational perspective; then what…?”.

And that’s what fundamentally makes us uncomfortable… because as I said earlier, we feel a moral imperative to prevent the harm from happening again. And it’s why we search for broken parts and people to blame. But as said by safety researcher David Woods, hindsight bias can make us think that ‘the past seems incredible’ and ‘the future looks implausible’; we ask ourselves, ‘how did they all not see the risk, why did they do nothing?’

It’s difficult to disregard our knowledge of the outcome of an event once it’s already happened, it’s much easier to play the classic blame game, define a “bad” individual, group, or organisation as the culprit, and stop our inquiry there.

In complex systems, things are a lot more grey.

As always, I hope this has helped you in your quest to know What to Ask and When to Act.

Sam

Be Curious. Be Kind. Be Brave.

Welcome!

I’m Samantha

I help board members succeed in the boardroom and make a positive impact on the health, happiness and resilience of society through their effective leadership and governance of safety, health and well-being.

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE…

FEATURED CONTENT

[text-blocks id=”4249″ plain=”1″]

Let us know what you have to say:

Want to join the discussion?Your email address will not be published.